Galerie Peter Herrmann |

- | Ancient Art from Africa |

||

|

Photo: Peter Herrmann |

| Thermoluminescence - Expertise | Head

Ife-Culture, Nigeria |

| Edited in the net since november 2024 |

Head of an important person: |

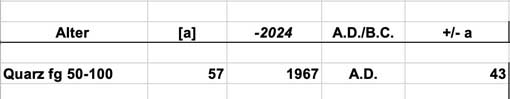

Each object also has its own story within the general context. This head was sold by a priest in Nigeria who asked his worshippers to bring him anything pagan from home. He would use it to travel to Lomé to raise money for the renovation of the church. The age of the head cannot be determined using classic thermoluminescence analysis, as it was repaired around 1967. In the process, the head was heated to such a high temperature that the measurable material of the cast core remains was reduced to zero |

|

If you are interested in the details of age determination, you can find a description from 2008 by Peter Herrmann that is still valid today here: Age classifications The head was mounted on a wooden frame for festivities and was fully clothed in life-size. The headdress began below the visible base. The repair was therefore not visible during the performances. You can see from the repair at the bottom right that the head has suffered a severe blow, resulting in a crack that extends almost to the back of the head. |

|

To prevent the crack from developing into the face and making the damage visible, the decision was made to repair it. This was carried out very professionally, as can be seen in the photograph of the interior. It is important to mention a few historical details in order to understand the assumptions. In 1967, no age determination by the TL was known. At that time, no foundryman could have known that a repair would make it impossible to determine the age using this method. The fact that the value of an object depends on its age was also unknown in Nigeria at the time. After visiting a workshop, the head of the family therefore decided on the basis of purely pragmatic technical aspects. This pragmatism is often lacking in scholarly books, which have a strong tendency to spiritualise objects and, if possible, try to increase their museum value by attributing as much as possible to kings. These views distort the view of Africa and here of Nigeria in two ways. It tends to exaggerate the spiritual value and, more importantly, ignores the existence of an urban middle class that could afford such artefacts. As a reminder, until around 1800/1850, the metal value of bronzes was roughly equivalent to that of gold. The fact that Ife heads were produced as forgeries with fake patination can only be assumed from around the 1990s onwards. An article with a detailed description of how the gallery owner with experience as a restorer uncovered a forgery can be found here: Made as a replica. The accusation of forgeries is of course older. But it related to originals that were not in the possession of museums. There was a self-created assertion that there could only be a few originals of royal origin. This was claimed in these circles to increase the value of their own inventory until they finally believed themselves. However, this has nothing to do with science. Here is a look inside the head with a view of the repair. |

|

It is probably an idealised depiction of a person of importance. The literature states that it is an Oni, king of Ife. The gallery owner is not so sure, because some of the heads have very feminine features in their resting aesthetic. Contrary to earlier descriptions, also on the gallery's website, which we have left unchanged for the time being for the sake of correctness, the application is far more profane. This head also comes from a private collection, so it is by no means from a palace, as ethnologists and, increasingly, female ethnologists with a longing for splendour and majesty, have been fabulating. Once again, the artisanal, artistic aspect is important. This non-monarchical background has nothing whatsoever to do with the quality of the workmanship. Cf. traditional literature rejected by P.Herrmann:: |

| Similar objects: | Illustration: |

| Federal Department of Antiquities, Lagos, Nigeria | Elsy LEUZINGER: Die Kunst von Schwarz-Afrika, Recklinghausen, 1972, S. 151. |

| Ife Museum für Ife-Altertümer | Schätze aus Alt-Nigeria. Ministerium für Kultur, Berlin (Ost) 1985, S. 116. |

Frank WILLETT: Ife. Metropole afrikanischer Kunst, Bergisch Gladbach 1967, S. 37. |

| British Museum, London |

William B. FAGG: Bildwerke aus Nigeria, München 1963, S. 39. |

Till Förster: Kunst in Afrika, Köln 1988, S. 2. |

| Ife Museum für Ife-Altertümer (Kopie) | Ekpo EYO, Frank Willett: Kunstschätze aus Alt-Nigeria, Mainz 1983, S. 21. |

|

| Detailed view. Evenly grown patina |